Neanderthal Lipstick

About matriarchy and the deep origins of lipstick and religion.

Matriarchal studies is the name given by Heide Goettner-Abendroth to the woman-centered historical research that she helped pioneer. I only became aware of this about a year ago myself, but since I’ve come to see it as absolutely essential to understanding both the origins and functioning of our contemporary culture and spirituality. The awareness of these discoveries is mostly absent from mainstream culture, however, so with this post I will try to give a quick summary of some of the most important insights and discoveries from this field. To do so, I’ll lean heavily on Heide Goettner-Abendroth’s book Matriarchal Societies of the Past and the Rise of Patriarchy (2022) and the website Matriarchalstudies.com. Henceforth I’ll also shorten Goettner-Abendroth’s name to HGA, so as to save myself the laborious typing of her long name.

In my previous post, I discussed the interweaving of feminism and the female symbolism of pre-patriarchal religion (and also whether matriarchal is the right word to use for it). In the introduction to her book, HGA acknowledges that there is a political element in her interpretation of the archeological and anthropological evidence: She would like this new story of the past to help women of today free their hearts and minds from the yoke of patriarchy. While that is understandable, considering all the gross misrepresentations of the past made over the years in the interest of building up men’s position and status, I think that certain parts of Western culture is now maturing enough into a general appreciation and understanding of women’s value and worth to let go of some of that assertiveness. I’ll pass over some of her conclusions that to me seem overly motivated by a desire to assign women agency and worth and try to focus on the core of her argument.

She identifies four main characteristics of these societies which I’ll expand on below, (spending most of the time on the last two):

Gift economy

Consensus-based political system

Matrilinear kinship

Culture oriented around the sacred

Gift economy

At first glance, it’s perhaps the economic organization of matriarchal societies that appear as their most radical aspect when compared to our contemporary, capitalistic system: It is based on generosity, reciprocity and gift exchange rather than accumulation and profit, and on usage rights to land and resources rather than exclusive ownership.

In such societies, the traditional domains of men has been hunting (which later became herding and construction) and politics. For women, it has been gathering (which later became agriculture) and economic distribution. The flow of resources is managed by older women and directed by rules and customs, such as the obligation of a wealthy clan to host a festival to distribute surplus food to the greater community. Status and wealth are strongly connected to gift-giving, meaning that potential economic inequality gets transformed into social prestige through gifting resources and treasures rather than hoarding them individually.

HGA writes: “It goes very much against our (current) way of thinking to imagine that (women’s) power of economic distribution could lead to a balanced economy where there are no rich and poor, and where general prosperity is the rule. But this reciprocity derives from the value system of matriarchal societies, where maternal behavior is seen as the prototypical activity: it therefore includes the maternal value of caring for and nurturing all members of the society, different as they may be, which means respect for diversity, and the value of equilibrium and balance among all segments of society.”

As David Graeber clearly showed in his book Debt: The First 5000 years (2011), these societies operated neither with barter (the exchange of one type of goods for another) nor with money or other forms of currency. The so-called shell money that often gets presented by historians as an early form of money was not used to buy food or other resources but rather to balance and enhance social relations, in connection with funerals, birthday celebrations, feasts, group initiations, and, particularly, weddings and resolutions of disputes.

Consensus-oriented political system

In matriarchal political systems, decision-making begins at the household level, where all clan members gather in councils to discuss domestic matters. This same consensus-based approach then extends to village-level governance, where male delegates from different clans come together to address community-wide issues. While men act as political delegates and representatives, there are significant limitations on their authority. They act as messengers and implementers rather than autonomous decision-makers. Because the origins of their authority lie in the consensus reached in their clan house, they must rely on mediation and diplomacy rather than commands and decrees.

The perhaps most clear indication of both the gift economy and the consensus-based politics is the egalitarian nature of burials. Before patriarchy, people were generally buried in community graves, not singled out in glorious individual burials along with treasures and weapons, which became common for the ruling elites after patriarchy. The examples of valuable items in graves that do exist in older times are just as likely, or even more, to be given to an invalid, an older woman, or a young child rather than a man at the height of his physical powers.

Matrilinear kinship

While the fact of motherhood is immediately obvious to anyone who witnesses the birth of a child, the concept of biological fatherhood is dependent on firm boundaries around women’s sexuality. For fatherhood to be clear, everyone involved has to be certain the woman has only slept with one man. As I’ll discuss in my next post, this development first occurred about 6000 years ago when humans turned to domesticated animals as the primary source of food.

Before this development occurred, HGA writes that “Given the open, often changing sexual relationships between women and men, it is not even clear that people knew the connection between conception and birth. They probably believed that women brought forth life from themselves—just like Mother Earth … who was seen as the guarantor of rebirth, gifted with a miraculous capability to turn death to life and return the dead to the world. These beliefs were held for hundreds of millennia, as the myths of primordial goddesses show, who brought forth children from themselves through parthenogenesis.

The view was that children came from ancestors and not from men; that is, the perspective was completely different. One of the first ethnologists among Trobriand Islanders still observed the belief that children did not originate from men, but from ancestor spirits returning to life through a young woman from the same clan. The facts of procreation were unknown to them. The same idea has been reported by the first explorer of the Mosuo, in which the children, when asked about their father, named their mother’s brother, as they were unfamiliar with the term of “father” and the concept of biological paternity. The worldwide rituals of retrieving ancestral souls from ponds, stones, and tombs practiced by women demonstrate the same view: children come from ancestors, not from biological “fathers,” and are reborn into life by women.”

With the generally open and often changing social and sexual relationships of early human cultures there were no blood relatives in the sense of how we think of it now. Africa’s oldest aboriginal peoples, the San and the Pygmies, even today do not organize their social life by genealogy but rather by age class. HGA writes: “Within each age class, members call each other “sister” and “brother,” referring not to blood kinship, but to the fact that they are of a similar age. Similarly, all women with children are collectively mothers, and the group of elderly women helping the mothers is collectively called grandmothers—or so-called by researchers, because we are so much accustomed to this concept. … To understand the Palaeolithic social order, a comparison with these aboriginal peoples of Africa is highly relevant. It supports the assumption that, at those (Paleolithic) times, too, life was organized around smaller or larger egalitarian groups within an age-class society.”

In all human societies at all times, the primary social group has been the mother and the child, which originates at birth and continues during a nurturing period that lasts for years. The mother line, on the other hand — matrilineality, the idea of the grandmother as the indirect origin of her grandchild — only emerged much later, in what is known as the Neolithic Era.

The Neolithic began as the climate stabilized after the massive upheavals of the Younger Dryas period. In a short window about 13,000 to 12,000 years ago, the climate see-sawed dramatically, global temperature at one point rose ten degrees celsius in 10 years, global sea levels rose more than 100 metres, and almost 75% of the megafauna on earth was wiped out along with much of mankind. The end of this period is marked by the establishment of the mysterious ritual site of Göbekli Tepe in the 10th millennium BCE — the first known sacred structures built by humans.

From the time excavations began in 1994 it has been an archaeological sensation that continues to upend the traditional understanding of the origins of civilization. Before its discovery, no one thought that semi-nomadic, hunter-gatherer types were capable of building much of anything, let alone something of that magnitude, with more than 200 pillars weighing between 4 and 20 metric tons, some at over 5 meters in height. Now it appears that the extensive, coordinated effort to build these structures was actually what laid the groundwork for the development of complex, permanently settled societies, rather than the other way around.

The archaeological finds show that it began as a hunter-gatherer’s seasonal religious festival of feasting and monumental construction. Over the course of almost two millennia of use and constant building work, people began to remain in place next to the building site for longer periods and, gradually, forming communities to organize themselves for the construction effort, which set off a vast transformation of their economic system in the process. What had been occasional, experimental cultivation of stocks of native wild grains now became deliberate practice, with hoe-agriculture implemented on a large scale. The enclosing and domestication of animals from the surrounding area soon followed, with the wild sheep and goats that were drawn to the grain fields being the first and cattle added later.

From the time of the first woven grass mats that protected against wind, sun and rain on the African savannah, up until the birth of patriarchy 250,000 years later, shelters, and later huts and houses were the domains of women. HGA writes: “We know of Mongolian peoples today where the yurts belong to the women. They transport them with pack animals from one place and erect them in another. The same is true of the nomadic Tuareg tents in the Sahara, which are the property of the women who weave them from goat hair. The construction and decoration of permanent clay dwellings among indigenous peoples in Africa and the Americas is solely women’s work. Women developed these skills, and the houses are theirs. The house itself is considered female and is decorated with attributes such as breasts and a vulva symbol at the entrance. Even linguistically, woman and house are identical, as examples from Africa show: the word axxam in the language of the Berbers means both woman and house, and the name of the Egyptian goddess Hathor means house of Horus. Such examples are so numerous that we can assume it was no different in the earliest epochs”.

(Here I have to pause for a moment just to express my own incredulity at men not being involved with building houses, since it seems like such a natural thing for a man to do. Men certainly became the principal builders in later times, but perhaps it really was a women’s activity at first, strange as it seems. )

In the new settlements with permanent houses around Göbekli Tepe and in nearby areas, children, and especially the daughters, remained with their mothers longer, continuing to stay in the home to help with agricultural tasks and domestic arts. As these groups expanded to include three or four generations living and working together under the same roof, a line from one daughter-generation to the next was identified, creating a female genealogy. This vertically intersected the earlier age classes, which now lost their importance. The men continued to live in their mother’s house, which was their birthplace, and thus, the eldest mother and her daughters, sons, and grandchildren occupied the same house or group of houses. Matrilineality became matrilocality, as residence in or near the mother’s house. Unrelated men could come to a different house for a limited time as friends or lovers of young women, but were only guests there with no rights or duties, and had their home in their own mother houses, where they bore the maternal clan name and had their obligations. This, then, is the basic idea of matrilinearity, which continued up until patriarchal times.

Culture oriented towards the sacred

We inherited the foundations of our culture and spirituality from our gentle, older cousins, the Neanderthals. Faint memories of these tall, hairy people might still be with us in the form of myths, such as the Basque basajaun, Norse trolls and the Himalayan yeti. Neanderthals came into existence about 300,000 years ago (100,000 years before we did) and went extinct about 40,000 years ago, around the same time that we went through our great evolutionary shift during the Upper Paleolithic transition. Their vocal organs were well-developed (which means that the development of language must have occurred much earlier, among the first people of the Lower Paleolithic Era, 2-4 million years ago), and they were well capable of symbolic and abstract thought:

Ochre is a natural clay earth pigment that contains iron oxide and has a reddish color that is reminiscent of living flesh and blood. It was the first pigment used by humans and has always symbolized life, as still seen today in the form of lipstick and sports cars. The Neanderthals developed the custom of sprinkling it on their dead, which Homo Sapiens adapted and continued to expand upon throughout the Palaeolithic. We dusted our dead ever more richly with it, painted it on graves and large surfaces in caves, and finally used it in everyday life for painting our skin and endowing ourselves and our treasured objects with life energy.

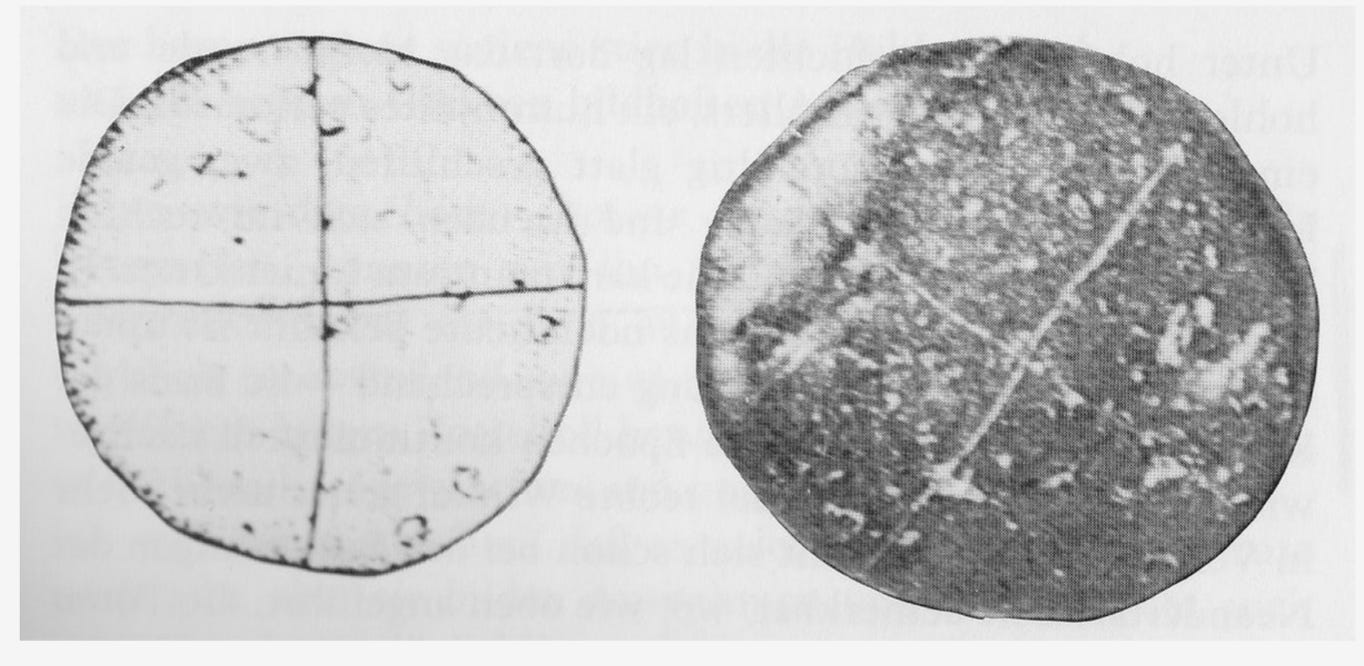

The Neanderthals also created the first abstract symbols that we know of, one of them being the cross. The first line of the cross is the horizontal east-west direction that the sun, the moon and all other celestial bodies takes across the sky every night and day, and the Neanderthals would bury their dead in a fetal position along this orientation.

HGA writes: “By adding a vertical north-south line, they achieved the first ordering of space — a great intellectual advance still reflected in our compass today. This four-sided spatial order was also expressed by an ideogram with four corners scratched in stone and bone: the quadrangle, in its simple or multiple forms. Crossed lines combined with a ring, or ring-cross, are even conceived as three-dimensional. The upper arch refers to celestial bodies, which move by day and night from east to west across the heavens. Yet the question remained: why do they always rise again in the east—how do they get there? In response, they imagined that the sun, moon and stars also traversed an invisible lower arch in the Underworld, which brought them back from west to east. The lower arch of the ring-cross represents this. The world’s three-dimensionality was expressed not only with the ring-cross but also with the sphere divided into an upper and lower hemisphere. This form they found in nature or reproduced themselves, which shows how meaningful it was for them. It represented space, divided into the vault of heaven and the vault below, with the Earth in-between.”

“From observing the heavens, in a further intellectual accomplishment, Neanderthals also created the first order of time. This is based on the three visible phases of the moon, which recur regularly at all the Earth’s latitudes, dividing the flow of time into equal parts. They also represented this temporal triad with ideograms scratched into bones and stone: three parallel marks or the abstract sign of a triangle. … From the triad, the number nine was developed, because each visible phase of the moon comprises three times three, or nine nights. Therefore, it could be seen for 27 nights. Add the one night of the invisible phase, and the result is a lunar month of 28 days. … Regular groups of three signs in bones could, therefore, be records of this counting method and thus of the first lunar calendar.”

Up until historical times, all art was religious, and there were two kinds: One was permanent art on the walls of caves and abris, consisting of scratch drawings, paintings, and bas-reliefs. The other was portable art, consisting of carved figurines and sculptures, as well as scratch drawings and paintings on bone, horn, and thousands of stones. Both types of art date from the beginning of the Upper Palaeolithic period, but portable art continued for longer and spread much further, including to areas where there were no caves. In addition, abstract symbols such as lines, dots, and line combinations such as net and crosshatch patterns appeared both in cave paintings and on portable objects. In a huge geographical area, for tens of millennia, these art forms used a homogenous system of symbols that perpetuated basic ideas from the Middle Palaeolithic.

There are two dominant themes in this art: on the one hand, animals, and on the other, women or vulvas. These appear in the monumental cave paintings just as they do in small portable sculptures. In caves, the drawings and paintings are generally in a hidden section, far to the back, which shows their separation from everyday life and makes them more sacred. These caves were thus symbolically ornamented "nature temples" and were used as central, fixed sanctuaries. Overall, the cave remained a sacred space even in later cultural epochs and was then artificially recreated in pyramids, temples, and even Gothic cathedrals. Movable sculptures, on the other hand, were portable relics that could be carried anywhere and set up for ceremonial celebrations or rituals.

The abstract vulva sign is one of the oldest and most common of all signs. The Neanderthals already scratched it into rock walls as a triangle with a short line ("slit") or cup ("hole") at the center. As humans began making female figurines during the Upper Palaeolithic, they always displayed a pronounced pubic triangle (whereas breasts may be ample, small or even lacking completely, depending on the given style), which continued on through all later epochs, even up to the present among some indigenous peoples. This triangle was both an ideogram for the moon and for the order of time.

Early on, the number three led to the concept of the lunar trinity, a threefold entity that is really only one, as reflected in the course of a pregnancy, which lasts for three times three or nine lunar months. This sacred connection between women and the moon is perhaps best expressed in the famous relief of the Venus of Laussel:

Her raised right hand is holding a bison horn with exactly 13 incisions. Due to its increasing and decreasing shape, the moon is generally depicted as a horn or as a pair of horns, and the 13 incisions correspond to the year's 13 lunar months. With her left hand, the woman is pointing to her womb as if to show that she also carries the temporal sequence of the moon in the sky in her body's menstrual cycle. With her left hand, the woman points to her womb as if to show that she also carries the temporal sequence of the moon in the sky in her body's menstrual cycle, and as an indication of her threefold nature, she is not alone but accompanied by two smaller figures in similar poses on nearby stones.

This symbolism of pregnancy, women and vulvas does not relate to a "fertility cult" but is the central symbolism of a religion of rebirth. The term that probably comes closest to their understanding of this might then be "Primordial Mother," since in this earliest religion, the concepts of earth, woman, moon, and the temporal sequence of life, death, and rebirth formed a symbolic continuum.

HGA writes: There are many examples among indigenous hunting peoples that support the interpretation that the animal world was also included in this rebirth religion. By placating the ancestral mothers or killed animals with song, dance, and other cultural gifts, they will send new animals, born again. … Among these indigenous peoples it is women who initiate men into rituals of the hunt and who watch over their hunting practice. Among the North American Iroquois there were two women’s hunting societies responsible for maintaining spiritual contact with the animals and teaching the hunters and fishermen correct and respectful behavior toward them, since otherwise the animal’s ancestral mothers would no longer send young animals back into this world from the world beyond. As keepers of death and rebirth, women were seen as mediators between the animals and hunters. According to the mythology of the indigenous Ainu in North Japan and on the Kurile Islands, it is Mother Earth whose daughters and sons are the land animals, and Mother Water who gives them the water animals. These goddesses once introduced the men to the hunting and fishing rituals so that they would carry out these activities respectfully—meaning that it was once the women who taught the men these rituals. Only when an animal soul comes home to its female animal ancestors with human gifts like songs and woodcarvings do they send further descendants for the hunt. All the hunting peoples of northern Asia share this belief, and it extends back into Palaeolithic times.

Especially significant in this context is a Palaeolithic rock drawing from the Tiout Oasis in the Sahara Atlas Mountains (Algeria) with a motif that occurs multiple times in Africa. It shows an elevated female figure with raised arms, perhaps in a ritual robe or with wings, looking toward a hunter with a bow and arrow. He is about to shoot an arrow at an ostrich. A line goes from the woman’s womb to the man’s genitals or navel; this has nothing to do with sexuality, but designates him as her son. The man with the bow and arrow symbol stands unambiguously for the theme of “death.” The motherly woman, on the other hand, whose vulva brought him forth, stands for the themes of “life” and “rebirth,” and not only human rebirth, but also that of all the animals surrounding her. At the same time, her raised arms show that, only with her permission and blessing, is he allowed to hunt and kill, and must do so “respectfully,” as the indigenous hunting peoples say.With her left hand, the woman points to her womb as if to show that she also carries the temporal sequence of the moon in the sky in her body's menstrual cycle, and as an indication of her threefold nature, she is not alone but accompanied by two smaller figures in similar poses on nearby stones.

But what about the men?

For the sake of keeping things relatively simple, I’m leaving this article off here at the beginning of the Neolithic period, 12,000 years ago, when the spiritual complexity increases with the advent of genealogy and agriculture.

There are many big questions to get into, one of which being the paleolithic masculine identity, which for so many years have been tossed around as the stereotypical dumb or brute club-wielding male. I’ll be exploring this in much more detail later, but for now let’s just say that the Paleolithic male identity in a greater cosmological sense probably was most closely related to our idea of the son.

What we see in this Paleolithic rock drawing, according to Heide Goettner-Abendroth, is “an elevated female figure with raised arms, perhaps in a ritual robe or with wings, looking toward a hunter with a bow and arrow. He is about to shoot an arrow at an ostrich. A line goes from the woman’s womb to the man’s genitals or navel; this has nothing to do with sexuality, but designates him as her son. The man with the bow and arrow symbol stands unambiguously for the theme of “death.” The motherly woman, on the other hand, whose vulva brought him forth, stands for the themes of “life” and “rebirth,” and not only human rebirth, but also that of all the animals surrounding her. At the same time, her raised arms show that, only with her permission and blessing, is he allowed to hunt and kill, and must do so “respectfully,” as the indigenous hunting peoples say.”

Another illustration of the matriarchal male identity is shown on the cover of Robert Graves’ The White Goddess (1948), the book that I gratefully acknowledge got me into this mess of an obsession to begin with! In this image we see man as a poet and philosopher, granted his birth, death, rebirth, and poetic vision by the Primordial Mother, of which he is also a part:

In my coming posts I will be exploring the changing relationship between men and women in the Neolithic and Mesolithic periods, the birth of patriarchy, and the general evolution of spirituality over time.

Thank you for your attention!

Absolutely fascinating! I’m making a lot of art these days that looks a bit like these cave drawings! I’d love to show you them sometime. Keep up the writing and I’ll keep reading!