That Time When Men Divorced The Earth

How climate change on the Steppe brought about the birth of Patriarchy.

“In this moment, thinking neither of good nor evil, who are you?”

- Huineng (638-713 CE)

In my last article, I explored the so-called matriarchal side of the early Stone Age (paleolithic) cultures: the reciprocal gift economy and consensus-based political system, the matrilinear (descended from the mother) kinship, and the cultural orientation around what we might call the Mother Heaven-and-Earth — the sacred feminine life force that was immanent in everything, and in which the cycles of death and rebirth played out. In this article, I want to explore how Patriarchy came around to change all that. To get there, however, I have to make two little detours, first to the Chinese Zen teacher Huineng, and then to the Neolithic.

Huineng

Huineng was originally an illiterate country boy from the south of China who, in the 6th century, traveled north to study with the Zen teacher Hongren. Due to his extraordinary abilities and perception, Hongren eventually decided to make him his successor and the sixth patriarch of the Chinese Zen tradition. But because he was a dark-skinned, uncultured man from the wrong part of the country — the equivalent of today’s immigrant Guatemalan day laborer in the U.S. or Syrian street food vendor in Europe — his monk colleagues became outraged when they found out he’d received the acknowledgment from Hongren, thinking that the honor should instead have gone to their preferred man of their own kind. Hongren had anticipated this reaction from them and, therefore, told Huineng to leave town and stay hidden for a few years until the ill tempers died down. The monks, however, were so enraged that they decided to set out in hot pursuit after Huineng, determined to get back the symbolic robe and bowl that Hongren had given him, and perhaps even to kill him in the process if need be. When one of them finally caught up to Huineng and made his demands, Huineng simply offered him the robe and bowl without resistance. The monk who had come into the situation so angrily hell-bent on justice being served was completely surprised by this. Suddenly, he was seized by confusion and couldn’t bring himself to pick up the items that had been so important to him just a moment before. That was when Huineng asked him his famous question: “In this moment, thinking neither of good nor evil, who are you?”

This attitude or state of being that Huineng embodied in that encounter is what Zen practice seeks to cultivate. It is also how I’d like to try to approach this look at history. Since it was first named more than a hundred years ago, and certainly in the last few postmodern decades, Patriarchy has been the undisputed bad boss. It is portrayed as the root cause of all the war and strife that has plagued Earth for the last few thousand years and the source of most of the rest of our problems. In a nutshell, if everyone would just realize how bad Patriarchy is, we would be able to return to a just and fair world where everyone lives in harmony with each other.

Perhaps that is true, and perhaps something else is also going on? The truth usually grows more layered and paradoxical the closer we look at it and the more curious we are. Borrowing Huinengs approach: In this moment, thinking neither that the matriarchy was good nor the Patriarchy bad, who were we? Who are we?

The Neolithic package

To understand how patriarchy came about, we first have to look at the cultural environment it came out of, which is the time-period we now call the Neolithic. To summarize thousands of years of highly advanced and complex civilizations in just a few sentences is, of course, both foolish and impossible, so although I don't think the following is completely wrong, please consider that it will be overly simplistic.

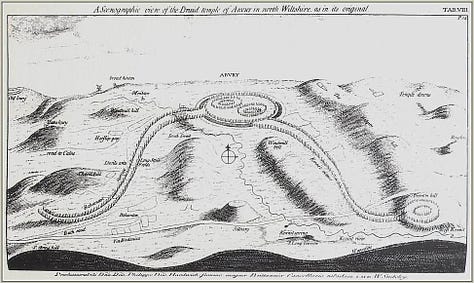

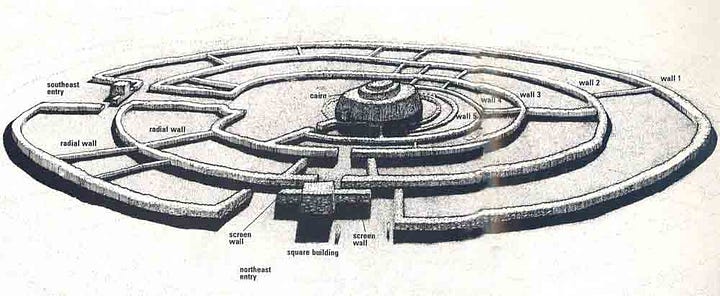

The neolithic began where my previous article left off, as the climate stabilized after the biblical floods and upheavals of the Younger Dryas period. This is when humans, for unknown reasons, began building the first religious structures, such as the famous Göbekli Tepe. These initial large-scale constructions were likely not planned and executed by societal elites but rather self-organized community efforts that served as the center point of the social and religious life of both local and regional communities. In the beginning, they took place as seasonal gatherings of feasting and building, but as the years went by, people remained in the same place longer and longer until they finally became permanently settled near the structures.

As I discussed previously, in the earlier Paleolithic age-class societies, every one of the same age thought of each other as sister or brother, and every old man or woman was a "grandparent" to every child in the group. While mothers have always known the identity of their child, the father-child connection and the idea of paternal kinship as we conceive of it today had still not been developed in the Paleolithic. In the Neolithic, as people remained in one house over multiple generations, the mother of the mother became identified, and the idea of genealogy along the mother's line (matrilineality) came forth, bringing with it the first conceptualization of history. The primeval mother ancestresses of the clans became the sacred mythical originators, a lesser or more local form of the sacred feminine principle that is the whole world.

In the earlier Paleolithic hunter-gatherer groups, the social structure seemed to have been flat and open in that people could freely move between groups, of which the membership simply being determined by whoever was present. By the change to genealogy, the clan replaced one’s age as the primary identity, and by people staying in one place, matrilocality also arose, the practice of continuing to live near one's mother.

As they remained in place, these first Neolithic cultures developed simple agriculture and domesticated the first animals, initially to supplement the traditional hunting and gathering, but over time, replacing it more and more. This new way of life, consisting of agriculture, domestic animal husbandry, weaving, pottery, and art, became the "Neolithic package." With the use of boats, it rapidly spread out through Europe and West Asia along seas and waterways. While there were occasional feuds between population groups at times of ecological pressure, the archaeology shows no signs of war at this time. Few or no wounds from weapons can be seen, and no defensive installations around towns and settlements beyond what was needed to keep wild animals or evil spirits out.

Despite the increasing cultural density and complexity, which saw some cities grow to tens of thousands of inhabitants, the layout of the settlements remained fundamentally egalitarian in nature over several millennia of cultural development. The villages, towns and cities were ordered according to kinship groups, what we call clans, living in longhouses centered around communal buildings or open spaces, which were used for political council meetings and religious gatherings.

The diverse, self-sufficient subsistence economy was in the hands of the women, who oversaw an equal distribution of goods within the clan structure. The men took care of construction and politics, perhaps herded the animals, and developed the metallurgy. Despite the increasing division of labor between men and women, the complimentary equality between the sexes seemed to have remained up until the patriarchal shift.

The Triple Goddess

According to Heide Goettner-Abendroth and her matriarchal studies perspective, the Paleolithic view of the sacred and feminine continued through this time period. The world both was and was ruled by the immanent and all-encompassing Mother Goddess in her three aspects (as originally identified by Robert Graves back in the 1940s), which were not separated from each other but interwoven through the cycle of the year and the life cycle of each being:

the White Goddess of the beginning as the creatrix of life (first aspect);

the Red Goddess as the maternal, nourishing bearer of life (second aspect);

the Black Goddess who brings the end of life and the transformation from death to rebirth (third aspect).

From this Neolithic triple goddess all the later Bronze Age goddesses of Heaven, Earth, and the Underworld are derived.

The Sacred King

The social identity of Neolithic women got obscured and partially replaced by later patriarchal ideas. Is it possible that something similar has been the case for men? If so, ccan a new understanding of male identity also draw upon the Neolithic for inspiration?

As I explored in this article, the feminism that arose in the mid-1800s was partially a result of the rediscovery of ancient Egyptian and Sumerian goddesses. An important catalyst for this was Johann Jakob Bachofen's book Das Mutterrecht (Mother Right, 1861), the first work to discuss the Neolithic position of women. Could a similar process have begun for men thirty years later, with James George Frazer's The Golden Bough (1890)?

In that book we find the first discussion of the Sacred Kings in the Neolithic, a flash of insight which has since been picked up by Robert Graves in The White Goddess, by David Graeber in The Dawn of Everything, by religious historian Mircea Eliade, and recently by a new crop of researchers and thinkers such as Eliseo Ferrer. As with women holding the central economic role in the clan household and the highest spiritual or religious positions, the men's role as the cyclical Sacred King appears to have been a cornerstone of Neolithic societies. These kings were understood to be the sons of the queen or the goddess and were deposed of in a dramatic ritual after a prescribed period of cyclical time — a year, eight years, twelve years, etc. Some of these kings may have actually been killed, their blood scattered over the fields, or more likely perhaps is that their body might have been symbolically eaten in a cannibalistic Eucharist that later became the familiar Christian custom.

Robert Graves wrote: "The tribal queen annually chose a lover among her entourage of young men, a king who had to be sacrificed at the end of the year, making of him a fertility symbol rather than an erotic pleasure object. His blood, once dead, was spread over the field so the trees, crops and flocks would bear fruit."

As agriculture, animal husbandry, human culture and cosmology were not separate domains but one continuous field, the purpose of sacrificing the king was to inject his energy and power into the cosmos and the land, thereby rejuvenating both the natural cycles and human cultural institutions. This ritual evolved over time and took on different expressions in different cultures. Substitutes were made for the actual regicide. Another man might be sacrificed in the king's place while the king hid out for a few days, he might abdicate the throne while an effigy was sacrificed in his place, and so on, but whatever form it took, the cyclical view of male power remained.

I'd like to return to these ideas in later posts and wrap up this brief overview of the Neolithic with a comment on its cultures' extraordinary consistency and longevity. Seen through the lens of our own times of rapid and extreme upheaval, the millennia of stability, continuity and homogeneity that these societies lived out are difficult to comprehend. Above all else, the Neolithic world seems to have been dedicated to nurturing and maintaining the health of cosmic polarity, the balance between masculine and feminine forces. This was most likely reflected throughout all aspects of their culture but is most visible to us today in the form of the extraordinary monuments they left behind. Hundreds of thousands of massive earthworks and megalithic monuments exist all over the world. In recent years, many studies have shown how their layouts often encode astronomical positions and alignments, and even make use of particular geological conditions to manipulate natural electromagnetic forces.

As these cultures lived according to a different set of values than our own today, I wonder if we are just now again becoming able to grasp the sophistication, or perhaps more importantly, the intention, of their efforts.

Perhaps, as the patriarchal imprints continue to fade in our collective imagination and we learn to appreciate less extractive ways of relating to the world, we will come to find inspiration for our own world in theirs.

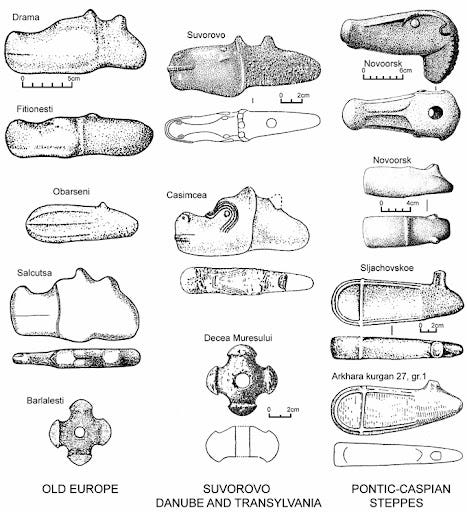

Patriarchy and climate disaster

In the late 1700s, while stationed in India, the British polymath William Jones (who by the end of his life reportedly knew 28 languages) noticed some striking similarities between Greek, Latin and Sanskrit, which led to the discovery of the indo-european language family. Over the years, many people contributed to exploring this shared ancestry, before it was synthesized in the 1950s by Marija Gimbutas into her Kurgan hypothesis or Steppe theory. While it was received with a lot of criticism at the time, it has since been supported by a mountain of evidence from historical linguistics, archaeology, anthropology, genetics, etc, and has now become a mainstream scientific theory. Briefly, the idea is that around 4000-6000 years ago, warrior-minded, patriarchal tribes pushed out of their homelands in the Eurasian steppe and entered into present-day Europe, India and China, gradually conquering, displacing or assimilating the more culturally advanced, egalitarian, and peaceful cultures they encountered there. To explore this I’ll use the book The Horse, The Wheel, and Language by David Anthony and the matriarchal studies of Heide Goettner-Abendroth.

The Eurasian Steppe is a broad belt of open grasslands stretching thousands of kilometers from Ukraine and South Russia in the west to Mongolia and North China in the east. To the north, it is bordered by the forests of Siberia and North Europe, and in the south, by the deserts and mountain ranges of West and Central Asia. It's been known as the Steppe Highway for its role in transporting goods, technologies and ideas between the East and the West, and by that same quality, it's had a long and inglorious history of setting up various invasions of China, Europe and India. However, the flat openness of the terrain that facilitates movement also creates an extreme climate of icy cold winters and blazing hot summers, and because these grasslands don't retain water as well as the forests to the north, they are more sensitive to larger shifts in temperature and humidity. As the climate has cycled between warm, humid phases and cold, dry ones over the millennia, it has had drastic effects on the life of plants, animals, and humans in this area.

During a prolonged warm period that lasted until the 6th millennium BC, the Eurasian Steppe became populated by neolithic people from the south and west who set up permanent settlements along lush creeks and riverbanks, with the aforementioned neolithic package lifestyle of simple agriculture, foraging, and small flocks of semi-domesticated animals, pottery, weaving and art. Around the 6th millennium, however, the climate began to cool and dry, and from about 4500 BC onwards, the ground turned barren, rivers dried up, and lakes shrunk or disappeared entirely. Many of the communities relocated or died out, and the few who survived the continuing catastrophe had to adopt a radical new way of life.

As the food from agriculture and foraging dwindled, the small flocks of sheep, goats and cattle that were previously kept close to the settlements got expanded into large herds that had to be moved around in search of pasture. People also increasingly turned to hunting wild horses for food, which over time led to them being tamed, and then one of the greatest discoveries of all time, that it was possible to ride them.

David Anthony writes: "Horses were first domesticated by people who thought of them as food. They were a cheap source of winter meat; they could feed themselves through the steppe winter when cattle and sheep needed to be supplied with water and fodder. After people were familiar with horses as domesticated animals, perhaps after a relatively docile male bloodline was established, someone found a particularly submissive horse and rode on it, perhaps as a joke. But riding soon found its first serious use in the management of herds of domesticated cattle, sheep, and horses. In this capacity alone, it was an important improvement that enabled fewer people to manage larger herds and move them more efficiently, something that really mattered in a world where domesticated animals were the principal source of food and clothing. […](#) A person on foot can herd about two hundred sheep with a good herding dog. On horseback, with the same dog, that single person can herd about five hundred. Riding greatly increased the efficiency and therefore the scale and productivity of herding in the Eurasian grasslands."

As these practices spread, a livestock breeding boom ensued around what is now the area of Kazakhstan. The already arid land came under pressure from the massively bigger herds, desertification increased, and the animals had to be driven longer and longer in search of pasture. These developments occurred in a relatively narrow historical window, between 5000 BCE and 4000 BCE, and produced several psychologically and spiritually drastic changes "all at once".

The First Warriors

Before this point in history, the role of the warrior did not yet exist. While men have always fought and feuded occasionally, this always used to be an exception rather than the rule. In the old system, while strong-bodied and capable men might lead others on a difficult hunt or take charge to protect the group through some dangerous situation, their authority would only last until the group returned from the seasonal hunt or the danger passed. As I mentioned above, in Neolithic societies, the day-to-day economic or political affairs of the communities were managed by elders and councils of elders through the clan system. However, as the climate situation on the Steppe kept deteriorating and the societal crisis it brought became the new norm, the authority of the strong man became institutionalized.

Abendroth writes: "The growing herds demanded ever larger pastures, and the new mobility on horseback enabled men to cover considerably longer distances for good grassland. This, however, led to a first phase of conflicts: as more and more tribes began to change to mounted grazing and thus were expanding, they clashed with each other over the areas they wished to claim, leading to disputes over grazing land. There were fights that, at this stage, consisted of feuds between clans and tribes. Also, cattle and horse theft began, perhaps for revenge or other motives. Such attacks could be carried out very quickly on horseback, retreating just as rapidly, but they resulted in like-for-like counter-attacks. … The increasing loss of good pasture land remained and became a permanent problem, resulting in constant feuding. Now the leaders were continuously needed, and their status began to consolidate: the figure of the "charismatic leader" evolved. … The leaders and their retinue of fighting men began forming their own groups and alliances beyond the cohesion of the clans and also beyond tribal boundaries. In this way, herders became herder warriors, and the areas within their reach sank into constant strife."

As soon as these cultures began managing large herds of cattle and sheep from horseback (around 5200–4800 BCE), their leaders were carrying maces – a stick with a heavy stone attached to one end — the purpose of which was to crack the skulls of rivals and cattle thieves.

David Anthony writes: “A mace, unlike an axe, cannot really be used for anything except cracking heads. It was a new weapon type and symbol of power.”

The threat of violence was what made it a symbol of authority, and in a more abstracted form it has been carried forward all the way up to our day, as the royal scepter.

Private property and Inequality

The need for constant, violent defense of the grazing herds would naturally have given rise to possessive and protective feelings, which over time coagulated and consolidated into the first ideas of private property. Unlike land or arable crops, cattle can be easily counted and, given the necessary skill, be multiplied at will, making for an ideal first form of mobile, personal property.

In the initial step, the competing clans would have had to differentiate between their own cattle and that of their neighbors, even if it meant the destruction and death of people who were just like them. In the second step, there was differentiation within each clan.

At first, the migration with the herds was a seasonal affair, as is still the case all over the world. The animals were kept close to the villages in winter, but in summer, they were moved to far-off pastures or high-lying mountain meadows. In these increasingly long months away from the village, the new warrior-herders formed a new social group identity, and the previous sense of collective ownership of the cattle was replaced by an individual one. The chiefs increasingly compensated themselves for their merits by owning livestock, for example, what they had taken from a rival tribe, and soon came to possess a large part of the herd. The previously redistributive communal feasts now became "feasts of merit," hosted by the chiefs and dependent on their offering and sacrifice of their personal animals.

Goettner-Abendroth writes: "Since the economy was based one-sidedly on livestock breeding, private ownership of cattle resulted in a significant shift of power in favor of the chief, enabling him to enlarge his retinue and strengthen the alliance between him as leader and his brothers in arms by giving away cattle. This relationship was sealed by oaths, thus legalizing inequality also between men for the first time, because not all men were included in the brotherhood of arms."

Over time, this societal split became the basic caste system that still persists in some parts of the world today, of Priests, Warriors/Rulers, Farmers (and later Merchants), and Slaves/Untouchables. In the archaeological record, this shift is clearly visible in the burial customs with the advent of the Kurgan grave for lone chief or king. Unlike the previous mostly unadorned community grave sites, Kurgans are huge mounds constructed over a grave with either a single male body or one surrounded by sacrificed slaves or family members, along with treasures, weapons, and horses. The kurgans themselves were built by cutting out the grass sod of the steppe and building a mound from it, as if the ruler was also taking his pasture land with him as his own property. For the largest of these kurgan structures, built by the Scythians in Chortomlyk in modern-day Ukraine, as much as 75 hectares of sod had to be dug up, the equivalent of 100 football pitches, or the exact size of Greenwich Park in London.

The Subordination of Cows and Women

Traditionally, hunting, herding, and building have been the domains of men, while foraging and agriculture have belonged to women. As climate change made rivers dry up and foraging and agriculture disappeared on the Steppe, women became increasingly dependent on men for food, and the social contract and balance between the sexes went through an unprecedented change.

Because the selective breeding of animals is so dependent on the applied knowledge of the male role in procreation, a great shift in the view of the function and importance of male sexuality must have taken place in the transition to a herding economy. In taming wild cattle and horses, the first step is to separate the more docile cows and mares from the more aggressive bulls and stallions, and by this practice, it would have been clear that no parthenogenesis was happening among the cows. A bull had to be let into the enclosure in order for the calves to come forth. Furthermore, where a good cow or mare can only have one pregnancy at a time and will rarely produce more than ten offspring, a good breeding bull or stallion can pass on their desirable traits to countless females. As they lived alongside herds of cattle for months on end, it’s easy to imagine the warrior chief beginning to identify with the bulls of his herd in this way.

As the environmental crisis continued to deepen, the men were forced to drive their flocks longer and longer away from the village, and so spent less and less time alongside women. The more the men stayed away from the village, the more they lived by rules and norms that women had no part in creating and that increasingly set the priests and warriors apart from the women, the cattle and the rest. Perhaps the transition was so slow or so marked by crisis and violence that no one noticed, but whether it was a sudden or gradual shift, at some point, a chief who was rich in cattle but poor in looks and personality must have made a previously unimaginable leap and offered some of his personal cattle in exchange for sexual intercourse with a woman.

It's easy to overlook how profound this shift was. For hundreds of thousands of years, whether wild or tamed, the cow with her moon-horns and life-giving udders had always symbolized The Great Mother of Heaven and Earth, or what we now call the cosmos or the universe. While in earlier times, cows were both hunted and milked, for a cattle bride price to become a possibility, both the cow and the woman would have to have been commodified and thereby also desanctified. Whereas before there had been some sort of sacred exchange, the value of women and animals was now determined by their worth to their owners, the men.

This way of quantifying and purchasing a woman's beauty and reproductive ability continued to gain popularity and soon became the new norm for relationships. Although men and women might have chosen to remain faithful to each other in previous times, it seems clear that monogamy as a cultural norm arose there on the Steppe in connection with the cattle-herder mindset of the bride price. They wanted exclusive usage of their own property, a guarantee that it was their own good warrior-traits that were being carried forward, and the loyalty of their own sons next to them as they went to war.

The final phase in the decline of women's status and importance came with the introduction of the wheel and the wagon.

Abendroth writes: "A third cold period afflicted the steppes of the Caucasus, the Caspian and the Black Sea in the 3rd millennium and destroyed any remaining agriculture. The forest steppe decreased extensively, the grass steppe dried out continuously, and deserts grew, jeopardizing the steppe peoples and leading to the Late Yamnaya in the Middle Bronze Age (2,800–2,600). References to houses and settlements now disappear completely. Apart from tents, covered wagons became the dwellings for the now fully nomadic herder warriors. Kurgan graves in the open Steppe show repeated occupations with long distances in between, indicating the people no longer remained at the site of their cemeteries. The herds had become too large to spend the winter at rivers and in swampland, and the herders now moved with them, also in winter, through the open country. Attacks and robberies by armed groups became commonplace and rampant. It is a way of life in which the women taken along lose all relevance. Apart from occasionally gathering wild grains, their main role was to milk the herds and produce dairy products, which means that they became dispossessed servants to care for the property of men. All that still belonged to the women was the tent or yurt, with the household the daughter inherited from her mother. Such deteriorating conditions led to a third wave of expansion from the Black Sea region to Europe."

Trade

Economic textbooks have traditionally speculated that money came about as a way to facilitate barter, the exchanging of one type of goods for another. In his book Debt: The First 5,000 Years, David Graeber argued that this idea is largely a myth and that there is no anthropological evidence that pre-patriarchal societies operated on barter systems. Instead, these economies were based on systems of credit and mutual obligations, where transactions occurred within social relationships rather than through quid pro quo exchanges.

In the suspicion and manipulation that surrounds us in our current cultural field, it is hard to even imagine that people in the past would travel long distances with heavy loads just to give it away as gifts to distant relatives. Yet, the evidence as Graeber presents it suggest that is more or less what happened.

Barter and money is to Graeber intimately connected with war and authoritative force, which is what came about for the first time in this cultural transition on the Steppe. So the same change that birthed endemic war, social inequality, the subordination of women and animals and men, also seems to be the source of “trade” as we understand it today,

Abendroth writes: "A "charismatic leader" was important not only for the feuds that flared up at any given time but also for the constantly changing alliances, which promised safety. Each new alliance was celebrated with feasts, with the newly allied chieftains competing to display their wealth—which probably filled their respective communities with pride. Finally, they reaffirmed their status by giving valuable gifts to each other. (At first) the gifts consisted of prestigious goods such as flint daggers, bracelets made of precious stones, shell jewelry, chains made of animal teeth, and also of copper and gold. … Copper was particularly regarded as "exotic" and highly valued, because (at first) they didn't produce the metal themselves but obtained it from the centers of copper processing of Southeast Europe. Such luxury goods as symbols of prestige spurred individual ambition, and so interest in owning them grew. A new greed for possession stirred, and the chiefs began to control the west-east transport routes by force of arms in order to monopolize the coveted copper. In this way, what we call "trade" was created, which is closely related to strife. Right from the start, trade appeared here as long-distance trade for individual interests."

A New Cosmos

All these changes to the way of life on the Steppe — ownership of animals and women, acceptance and legalization of inequality, permanent conflict with other groups - was reflected in and made sense of by a whole new cosmology and a new vision of what happened after death.

To my mind, at least, it seems obvious that Paleolithic and Neolithic cultures must have been organized around an idea of rebirth, which is that, at death, everyone went down to the underworld, from where they were later reborn as fresh, new beings. Just as plants die into the ground and come back up again, and as the sun and moon disappear below the horizon and come back again each day, so the same must be true for people and animals. This underworld was not necessarily a scary or gloomy place but perhaps something more like the pregnant belly of the Goddess-nature of the world — a sacred realm of returns and new beginnings.

Over the many centuries of separating themselves ever more from their women, the Indo-European warrior-herder left behind this female-directed rebirth religion. There can be neither birth nor rebirth without some kind of feminine being involved, and the feminine is almost completely absent from early Indo-European cosmology.

The Rigveda is the oldest collection of Vedic Sanskrit hymns, an Indo-European oral tradition that was written down sometime between 1500 and 1200 BCE in the present-day area of Pakistan. Out of its 1028 hymns, only 40 are dedicated to its most prominent female character, the goddess of the dawn Ushas, and only 3 to the next most important, the goddess of the Saraswati river. The previously supreme Cosmic Mother Goddess Aditi has no hymns dedicated to her. On the other hand, the hero Indra has 250 hymns dedicated to him and his sidekick Varuna 46. The fire-god Agni gets 200 hymns, and the intoxicating Soma drink 123 hymns.

This then brings us back to the title of this post, When Men Divorced The Earth. As they left behind women and the rebirth-goddess, these priests and warriors adopted a new cosmology to reflect their new reality, the Father god standing over the Mother. The term "God the Father" exists in all Indo-European languages (Sanskrit: "dyaus pitar," Greek: "zeus pater," Latin: "deus pater," and also "Ju-piter") and is derived from the early Indo-European root "dyeus pater", or "Father Sky".

In my next article, I will continue to explore that new Patriarchal cosmology, which has continued as the backbone of our Western culture to this day. Fundamentally it is the separation between Heaven and Earth, between right and wrong and good and evil — the way of thinking and being that the later wisdom traditions sought to move past, and that Huineng gives voice to by asking, “In this moment, thinking neither that some things are good and some are evil, who are you?”

Thank you for your attention!

__________________________

In the interest of making this more accessible for more readers, and easier for myself to actually publish, I decided against detailed footnotes, but that being said, here are my main sources:

Matriarchal Societies of the Past and the Rise of Patriarchy: West Asia and Europe, Heide Goettner-Abendroth, 2022

The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World, David W. Anthony, 2007

Debt: The First 5,000 Years, David Graeber, 2011

The Dawn of Everything, David Graeber and David Wengrow, 2021

The White Goddess, Robert Graves, 1948

The Origins of Fatherhood, Sebastian Kraemer, 1991

Thank you so much for your extremely well-thought-out and well-written analysis of this most critical period of our long-covered up history!

I wrote a book about this, Before War, which your friend Gunnar is listening to, and pointed me your way. Firstly, I agree that nothing in life is oversimplistic and black and white, hence I avoid using the words "good" vs "bad" .. but .. if we *were* to for the sake of argument .. isn't it unequivocally true that war, inequality and oppression of women and animals, which as you say result from patriarchy, are "bad"? Really bad, if you're on the receiving end? could we not therefore agree that matrilineal egalitarianism of the Paleolithic and Neolithic were, well, comparatively speaking, "good"?

Second, I notice an accidental deletion at the phrase "one place, matrlineality also" and I would love to know what you were going to say!

I for one am skeptical about the hard evidence for Neolithic king sacrifice, or human sacrifice in general. Is Frazier the root source of this idea? If so it's quite old before rigorous academic evidence. I've never seen archaelogical evidence for it in the Neolithic, first I've seen is in late Minoan times during the cataclysm crisis. It could possibly be a patriarchally-introduced idea that became a part of later matrilineal holdout societies the same way that social inequality did. I've really looked around for this as so many people seem quite confident that human sacrifice was an ancient custom in goddess cultures. Of course we see it in much later Iron Age Celtic societies with a strong connection to ancient animism, and has come down to us in mythology, but we can't project that backwards thousands of years with confidence.

I'd like to clarify the passage about the creation of "trade", given that, in the strict meaning of that word, trade was huge during the Neolithic, at very long distances. The difference that happened during patriarchy, as you point out, was that now it was for personal hoards of important families, rather than for sacred or beautiful items for all.

The other thing I would be so eager to see more evidence for was for male roles during the Neolithic. There is no reason at all to assume a male role in politics. The earliest clues we have, Minoan art, show women in leadership positions, while men are depicted mostly naked and worshipful of the women. Even for construction, there are matrilineal groups in which women exclusively take care of this, though my gut instinct is that this has more often in more cultures been a male role for good reasons. The metallurgy thing though, has been a huge mystery I have spent countless hours pouring over dusty volumes for a clue to. It's clear from the artistic evidence that women were solely associated with weaving, ceramics, and priestessing. But I have never been able to find anything about the origins of metallurgy. It's shrouded in mystery! It's never depicted in art! I'm fascinated if you have seen anything on this and something to link it to men. It would make sense for men to do it, since it was probably toxic to fetuses. It would also make sense for men to be the herders, since larger size and strength helps with larger animals, and since men were associated in ancient art with animals, but I haven't seen any direct evidence for it.

Thanks so much! Subscribed and will read more.